|

The Kata of Okinawa Isshinryu

Karate-do

An Informal Discussion

on their Possible Origins

©2000, Joe Swift, Tokyo,

Japan

|

Since its official

announcement in 1956, Okinawa Isshinryu Karate Kobudo

has spread throughout the world, with dojo in most continents.

There have since been many books, articles, and videos

published on the system in the English language. However,

more often than not, these materials utilize the same

sources for their research, with little, if anything

written based upon research of primary materials, that

is, Japanese language books on karate-do by Okinawan

researchers.

This article will attempt to trace the origins of the

Isshinryu kata utilizing mainly these types of primary

materials, in the hopes that it will clear the air of

some of the myths and misinformation that have plagued

the English-speaking Isshinryu community for literally

decades.

Seisan no Kata

Meaning 13, some people refer to it as 13 hands, 13

fists, or 13 steps. Customarily taught in both Shuri

and Naha, this kata, following the tradition of

Kyan

Chotoku, is the first kata the Isshinryu student

learns.

It is unclear exactly what the number 13 actually represents.

Some think it was the number of techniques in the original

kata; some think it represents 13 different types of

"power" or "energy" found in the kata; some think it

represents the number of different application principles;

some think it represents defending against 13 specific

attacks; and some think that it is the number if imaginary

opponents one faces while performing the kata. Out of

all these theories, this author must disagree with the

last, as it is highly unrealistic that kata teaches

one to handle such situations. On the contrary, kata

was designed to teach the principles needed to survive

more common self-defense situations, rather than a long,

drawn out battle against several opponents (Iwai, 1992).

Kinjo Akio, noted Okinawan karate researcher and teacher

who has traveled to China, Hong Kong and Taiwan well

over 100 times for training and researching the roots

of Okinawan martial arts, maintains that this kata originally

had 13 techniques, but due to a long process of evolution,

more techniques were added to it (Kinjo, 1999). He also

maintains that the Okinawan Seisan kata derives from

Yong Chun White Crane boxing from Fujian Province in

Southern China.

It is unsure who brought this kata to Okinawa, but we

do know that in 1867, Aragaki Seisho (1840-1920), a

master of the Chinese-based fighting traditions (Toudi)

demonstrated this kata (among others) in front of the

last Sappushi, Zhao Xin (Tomoyori, 1992; McCarthy, 1995,

1999).

The main lineages that include Seisan include those

passed down from Matsumura Sokon, Kyan Chotoku, Aragaki

Seisho, Higaonna Kanryo, Uechi Kanbun, and Nakaima Norisato,

among others. Shimabuku learned this kata from Kyan.

Both the Kyan and the Shimabuku versions of this kata

strongly resemble the Matsumura no Seisan (see Sakagami,

1978).

The "Master Seishan" theory, which claims that the kata

was brought from China to Okinawa by a Chinese martial

artist named Seishan (or Seisan) is uncorroborated myth

at best, probably propagated by well-meaning, but not-so-well-researched

American Isshinryu instructors. This legend cannot be

found in any of the literature coming out of Okinawa

or Japan.

Seiunchin no

Kata

This kata seems to have been brought to Okinawa by

Higaonna Kanryo, who is said to have learned it

under the master Ruru Ko, or perhaps under Wai Xinxian,

who is said to have taught at the old Kojo dojo at Fuzhou

City in Fujian Province. Recent research has indicated

that Ruru Ko was actually Xie Zhongxiang, founder of

Whooping Crane boxing, but this kata is not included

within that style, thus hinting that Higaonna had either

learned it elsewhere, or else developed it himself.

However, here we run into a problem, as Nakaima Norisato

(founder of Ryueiryu) is also said to have learned this

kata under Ruru Ko. Another theory is that Miyagi may

have been responsible for creating this form or introducing

it from other sources.

The word Seiunchin is written as "Control, Pull, Fight"

by many Okinawa Goju-ryu stylists, as well as Isshinryu

teacher Uezu Angi (son in law of Shimabuku Tatsuo),

perhaps hinting at the various grappling and grabbing

techniques contained within. A good example is the "reinforced

block" which can actually be applied as a wrist-crushing

joint lock (Tokashiki, 1995), and the "archers block"

which can be used as a throw (Higaonna, 1981; Kai, 1987).

Otsuka Tadahiko, a Gojuryu teacher who has spent considerable

time in China and Taiwan researching the roots of his

system, tells us that his research indicates Seiunchin

may mean "Follow-Move-Power" which would be pronounced

Sui Yun Jin in Mandarin Chinese (Otsuka, 1998). Kinjo

Akio says that his research has revealed to him that

Seiunchin may be from a Hawk style of Chinese boxing,

and mean "Blue-Hawk-Fight" which is pronounced Qing

Ying Zhan in Mandarin, or Chai In Chin in Fujian dialect

(Kinjo, 1999).

This kata is preserved in many modern styles of karatedo,

including Gojuryu, Shitoryu, Isshinryu, Shoreiryu, Kyokushin,

Shimabuku Eizo lineage Shorinryu, Ryueiryu, etc.

Naihanchi no Kata

Naihanchi (a.k.a. Naifuanchi) is typical of in-fighting

techniques, including grappling. There are three kata

in modern (i.e. post 1900) karate, with the second and

third being thought to have been created by

Itosu

Anko (Iwai, 1992; Kinjo, 1991a; Murakami, 1991).

Another popular theory is that originally the three

were one kata, but were broken up into three separate

parts by Itosu (Aragaki, 2000; Iwai, 1992).

This kata was not originally developed to be used when

fighting against a wall, but this does not preclude

such interpretations. While the kata itself goes side

to side, the applications are more often than not against

an attacker who is in front of you, or grabbing at you

from the sides or behind. Some say that the side-to-side

movement is to build up the necessary balance and physique

for quick footwork and body-shifting (Kinjo, 1991b).

Interestingly, most versions of Naihanchi start to the

right side, including Itosu, Matsumura and Kyan's versions.

Isshinryu's Naihanchi starts to the left. There are

others that start to the left as well, including that

of Kishimoto Soko lineage schools like Genseiryu and

Bugeikan (Shukumine, 1966), the Tomari version of Matsumora

Kosaku lineage schools like Gohakukai (Okinawa Board

of Education, 1995), and Motobu Choki's version (Motobu,

1997). This last may account for Shimabuku Tatsuo beginning

his Naihanchi to the left.

Isshinryu Naihanchi is basically a re-working of the

classical Naihanchi Shodan, in order to keep it in line

with the principles around which Shimabuku built his

style. The main reason Shimabuku did not retain Naihanchi

Nidan and Sandan is probably because his primary teacher

Kyan did not teach them (Okinawa Prefectural Board of

Education, 1995).

Wansu no Kata

This kata is said by many to have been brought to Okinawa

by the 1683 Sappushi Wang Ji (Jpn. Oshu, 1621-1689).

It is possible that it is based upon or inspired by

techniques that may have been taught by Wang Ji.

The problem with this theory is that why would such

a high ranked government official teach his martial

arts (assuming he even knew any) to the Okinawans? Also,

Wang Ji was only in Okinawa for 6 months (Sakagami,

1978).

Wang Ji was originally from Xiuning in Anhui, and was

an official for the Han Lin Yuan, an important government

post (Kinjo, 1999). In order to become an official for

the Han Lin Yuan, one had to be a high level scholar,

and pass several national tests (Kinjo, 1999). Just

preparing for such a task would all but rule out the

practice of martial arts, just time-wise. However, assuming

that Wang Ji was familiar with the martial arts, the

Quanfa of Anhui is classified as Northern boxing, while

the techniques of the Okinawan Wansu kata are clearly

Southern in nature (Kinjo, 1999).

So, if Wansu was not Wang Ji, just who was he? This

is as yet unknown. However, in the Okinawan martial

arts, kata named after their originators are not uncommon.

Some examples include Kusanku, Chatan Yara no Sai, and

Tokumine no Kon. It is entirely possible that this kata

was introduced by a Chinese martial artists named Wang.

As the reader probably already knows, in the Chinese

martial arts, it is common to refer to a teacher as

Shifu (let. Teacher-father). Could not the name Wansu

be an Okinawan mispronunciation of Wang Shifu (Kinjo,

1999)?

Other schools of thought are that Wu Xianhui (Jpn. Go

Kenki, 1886-1940) or Tang Daiji (Jpn. To Daiki, 1888-1937),

two Chinese martial artists who immigrated to Okinawa

in the early part of the 20th Century, may be responsible

for the introduction of the Wansu kata (Gima, et al,

1986). As a side note, Wu was a Whooping Crane boxer

and Tang was known for his Tiger boxing. They were both

from Fujian.

Shimabuku is believed to have added on several techniques

to this kata, such as the side kicks, evasive body movement

into double punches, and elbow smash as these are not

found in any other version of Wansu known in Okinawa

karate.

Chinto no Kata

This kata is said to have been taught to Matsumura Sokon

by a Chinese named Chinto, but this legend cannot be

corroborated. According to a 1914 newspaper article

by Funakoshi Gichin (1867-1957, founder of Shotokan

karatedo), based upon the talks of his teacher Asato

Anko (1827-1906), student of Matsumura Sokon):

"Those who received

instruction from a castaway from Annan in Fuzhou, include:

Gusukuma and Kanagusuku (Chinto), Matsumura and Oyadomari

(Chinte), Yamasato (Jiin) and Nakasato (Jitte) all of

Tomari, who learned the kata separately. The reason

being that their teacher was in a hurry to return to

his home country." (sic, Shoto, 1914).

It is believed by this author that the "Matsumura" in

the above excerpt is a misspelling of Matsumora Kosaku,

of Tomari. The fact that Matsumora Kosaku, is evidence

that Matsumora may have also been taught this kata as

well (Kinjo, 1999).

Now, what exactly is Chinto? There appears a form called

Chen Tou in Mandarin Chinese (Jpn. Chinto, lit. Sinking

the Head) in Wu Zho Quan (a.k.a. Ngo Cho Kuen, Five

Ancestors Fist), which was a style popular in the Quanzhou

and Shamen (Amoy) districts of Fujian (Kinjo, 1999).

Chen Tou refers to sinking the boy and protecting the

head. In the Okinawan Chinto kata, this is the first

technique, but in the Five Ancestors Fist it is the

last (Kinjo, 1999). However, this being said, this author

has yet to see the Chen Tou form to make a comparative

analysis. It is, however, worthy of further investigation.

There are 3 distinct "families" of Chinto in modern

Okinawan karate: Matsumura/Itosu lineage (performed

front to back), Matsumora Kosaku lineage (performed

side to side), and Kyan Chotoku lineage (performed on

a 45 degree angle). Looking at technical content, we

can see that the Matsumora and Kyan versions are nearly

identical, which is only natural since Kyan learned

this from Matsumora.

Sanchin no Kata

This kata has been described by many writers as the

original exercise that Bodhidharma taught to the monks

at the Shaolin Temple. However, this theory has no substantive

proof either way, so this actually remains nothing more

than speculation.

At any rate, the Okinawan versions of Sanchin have their

origins in the Quanfa originating from Fujian Province,

where many, if not most, Quanfa styles have a form of

this name. In fact, the term Sanchin (written as "three

battles" in kanji) seems to be found only in Fujian-based

Quanfa systems, as forms of this name are not found

in the martial arts of other areas (Kinjo, 1999).

Many researchers, especially from the Gojuryu tradition,

credit Higashionna Kanryo with bringing back Sanchin

from his studies in China (Higaonna, 1981; Kai, 1987).

However, there is evidence that Sanchin had existed

in Okinawa since before Higashionna's voyage to Fujian

and was passed on by Aragaki Seisho, who was Higashionna's

first teacher (Iwai, 1992; Okinawa Prefectural Board

of Education, 1995).

Higashionna's teacher in Fujian is believed by many

to be Xie Zhong Xiang, founder of Whooping Crane boxing

(McCarthy, 1995; Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education,

1995; Otsuka, 1998; Tokashiki, 1995), although there

is opposition to this theory (Kinjo, 1999). Higashionna

is believed to have learned the Happoren form from Xie,

which is said to be the basis for the modern Gojuryu

version of Sanchin (Otsuka, 1998). Higashionna probably

integrated concepts from Happoren to the Sanchin he

learned under Aragaki. When practicing Happoren alone,

however, the breathing is silent (Otsuka, 1998).

In either case, Higashionna had his students spend several

years on Sanchin alone before allowing them to move

on to the other kata he taught. Higashionna apparently

taught Sanchin as an open hand kata at first, with fast

breathing, but later changed it to a slower, closed

fist version (Higaonna, 1981; Murakami, 1991). Others

give Miyagi Chojun credit for closing the fists and

slowing down the breathing (Kinjo, 1999).

One provocative account survives about the importance

of Sanchin in Higashionna Kanryo's teachings:

"When I was still a child, I wanted to see the

karate of the famous Higashionna Sensei, even if only

once. So I went to the place he was teaching. However,

no matter when I went, I never saw Higashionna Sensei

perform karate. His students were practicing only Sanchin

with all their might, and Higashionna Sensei was instructing

them." (sic, Murakami, 1991, pp. 133)

The three of Sanchin is often described in English as

the battles between mind, body and breath. Other descriptions

refer to attack and defense on the three levels, i.e.

the upper, middle and lower levels (Kinjo, 1999; Otsuka,

1998; Tokashiki, 1995). The three important points of

Sanchin have been described as the stance, the breathing

method and the spirit, and if any one of these three

are lacking, one will not be able to master Sanchin

(Higaonna, 1981).

Higashionna Kanryo's Sanchin features two turns, and

only one step back. In order to remedy the lack of backward

stepping,

Miyagi Chojun created a shorter version of the kata,

featuring no turns, and two steps backwards (Higaonna,

1981). It is this version that Shimabuku Tatsuo utilized

in his Isshinryu system.

Kusanku no Kata

Often described in Isshinryu as a "night fighting kata,"

this form was passed down from Kyan Chotoku to Shimabuku

Tatsuo. Interestingly enough, no references to night

fighting are found in the primary references coming

out of Japan and Okinawa, leading this author to conclude

that such interpretations were contrived to fit movements

that are not very well understood.

In the year 1762, a tribute ship sent to Satsuma from

Ryukyu was blown off course during a storm, and ended

up landing at Tosa Province in Shikoku, where they remained

for a month. The Confucian scholar of Tosa, Tobe Ryoen

1713-1795), was petitioned to collect testimony from

the crew. The record of this testimony is known as the

Oshima Hikki (literally "Note of Oshima", the name of

the area of Tosa where the ship had ran aground). In

this book, there is some very provocative testimony

by a certain Shionja Peichin, describing a man from

China called Koshankin, who demonstrated a grappling

technique (McCarthy, 1995; Sakagami, 1978).

It is commonly accepted that this Koshankin was the

originator of the Okinawan Kusanku kata, or at least

inspired it. However, there are several unknowns in

this equation. First of all, was Koshankin his name

or a title, or even a term of affection towards him?

Second, if it was a title or term of affection, what

was his real name? Thirdly, what martial art(s) did

he teach, and how do they differ from the modern karate

kata of Kusanku? Most of these questions are still being

researched by this author and others.

For now, suffice it to say that Kusanku is a highly

important kata in the Okinawan martial arts, and has

spawned many versions over the years. Some of them include

the Kusanku Dai/Sho Itosu Anko lineage styles, the Chibana

no Kusanku of Shudokan, the Takemura no Kusanku of Bugeikan

and Genseiryu, the Kanku Dai/Sho of Shotokan, the Shiho

Kusanku of Shitoryu, and the Yara no Kusanku of Kyan

Chotoku lineage styles, including Isshinryu. Of course,

there are numerous others as well.

Kyan Chotoku is said to have learned Kusanku in Yomitan

under a certain Yara Peichin (Nagamine, 1975; 1976).

It is unknown at this time whether there is a familial

relationship between this Yara Peichin and the Chatan

Yara who is believed to have studied under Koshankin

during his mid-18th century visit to Okinawa.

Sunsu no Kata

This kata was created by

Shimabuku

Tatsuo, although it is still unclear as to exactly

when he created it. It is often described as a combination

of techniques and principles from the other seven Isshinryu

karate kata. However, there are elements of other kata

as well, such as Useishi (Gojushiho) and Passai that

Shimabuku is thought to have learned under Kyan.

There is also one sequence that appears as if it came

out of Pinan Sandan. However, Shimabuku's teachers appear

not to have taught the Pinan kata, so we are faced with

the problem of where he learned them. However, looking

at the timeframe in which Shimabuku was active, it becomes

clear that he could have learned the Pinan just

about anywhere, or even just taken the technique via

observing the Pinan kata being performed.

There seems to be some confusion as to what the name

Sunsu means. It has been stated that it means either

"strong man" (Uezu, et al, 1982) or "son of old man"

(Advincula, 1998). However, a recent newspaper article

from Okinawa tells us a different story:

"It is said that when Shimabuku performed Sanchin

kata, he appeared so solid that even a great wave would

not budge him, like the large salt rocks at the beach,

and his students nicknamed him "Shimabuku Sun nu Su"

(Master of the Salt) out of respect." (sic, Ryukyu Shinpo-sha,

1999, p.9)

Another possibility is that Sunsu may be named after

a family dance of the Shimabuku family (Advincula, 1999).

No matter what the meaning, it is safe to say that Sunsu

kata represents the culmination of Shimabuku's understanding

of the principles of the defensive traditions, and was,

along with Isshinryu, his unique contribution to the

classical art of Okinawa karatedo.

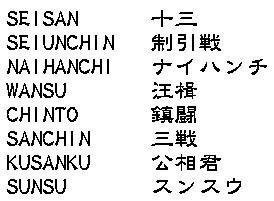

Table One:

The Kata of Okinawa Isshinryu Karatedo

Table Two:

The Lineage of Isshinryu Kata

|

SEISAN

|

Matsumura

Sokon - Kyan Chotoku - Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

|

SEIUNCHIN

|

Higashionna

Kanryo(?) - Miyagi Chojun - Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

|

NAIHANCHI

|

Matsumura

Sokon - Kyan Chotoku - Shimabuku Tatsuo

Matsumora Kosaku - Motobu Choki - Shimabuku

Tatsuo

|

|

WANSU

|

Maeda Peichin

- Kyan Chotoku - Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

|

CHINTO

|

Matsumora

Kosaku - Kyan Chotoku - Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

|

SANCHIN

|

Higashionna

Kanryo - Miyagi Chojun - Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

|

KUSANKU

|

Yara Peichin

- Kyan Chotoku - Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

|

SUNSU

|

Created by

Shimabuku Tatsuo

|

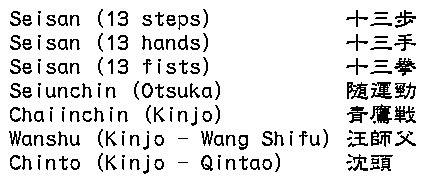

Table Three: Alternative Kanji for Kata as Specified

in the Text

Bibliography

Advincula, A.J. (1998) "Tatsuo

Shimabuku: The Dragon Man of Isshinryu Karate."

Advincula, A.J. (1999) Personal Communication.

Aragaki K. (2000) Okinawa Budo Karate no Gokui (The

Secrets of Okinawa Budo Karate). Tokyo: Fukushodo.

Gima S. and Fujiwara R. (1986) Taidan: Kindai Karatedo

no Rekishi wo Kataru (Talks on the History of Modern

Karatedo). Tokyo: Baseball Magazine.

Higaonna M. (1981) Okinawa Gojuryu Karatedo I.

Tokyo: Keibundo.

Iwai T. (1992) Koden Ryukyu Karatejutsu (Old Style

Ryukyu Karatejutsu). Tokyo: Airyudo.

Kai K. (1987) Seiden Okinawa Gojuryu Karatedo Giho

(Techniques of Orthodox Okinawa Gojuryu Karatedo).

Miyazaki: Seibukan.

Kinjo A. (1999) Karate-den Shinroku (The True Record

of Karate's Transmission). Naha: Okinawa Tosho Center.

Kinjo H. (1991a) Yomigaeru Dento Karate: Kihon (A

Return to Traditional Karate: Basics). Video Presentation.

Tokyo: Quest Ltd.

Kinjo H. (1991b) Yomigaeru Dento Karate: Kata I,

Naifuanchi 1-3, Pinan 1-5 (A Return to Traditional Karate:

Kata I). Video Presentation. Tokyo: Quest Ltd.

McCarthy, P. (1995) Bubishi: The Bible of Karate.

Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle, Inc.

McCarthy, P. (1999) Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts

Vol. 2. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle, Inc.

Murakami K. (1973) Karatedo & Ryukyu Kobudo.

Tokyo: Seibido.

Murakami K. (1991) Karate no Kokoro to Waza (The

Heart and Techniques of Karate). Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu

Oraisha.

Nagamine S. (1975) Okinawa no Karatedo. Tokyo:

Shin Jinbutsu Oraisha.

Nagamine S. (1986) Okinawa no Karate Sumo Meijin-den

(Tales of Okinawa's Karate and Sumo Masters). Tokyo:

Shin Jinbutsu Oraisha.

Nakamoto M. (1983) Okinawa Dento Kobudo: Sono Rekishi

to Tamashii (Traditional Okinawan Kobudo: Its History

and Spirit). Okinawa: Bunbukan.

Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education (1994). Karatedo

Kobudo Kihon Chosa Hokokusho (Report of Basic Research

on Karatedo and Kobudo). Okinawa: Nansei.

Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education (1995). Karatedo

Kobudo Kihon Chosa Hokokusho II (Report of Basic Research

on Karatedo and Kobudo II). Okinawa: Nansei.

Otsuka T. (1998) Chugoku Ryukyu Bugeishi (Chronicle

of Chinese and Okinawan Martial Arts). Tokyo: Baseball

Magazine.

Ryukyu Shinpo-sha (1999) "Isshinryu Karate". Ryukyu

Shinpo, 22 July 1999, p. 9.

Sakagami R. (1978) Karatedo Kata Taikan (Encyclopedia

of Karatedo Kata). Tokyo: Nichibosha.

Shoto (Funakoshi Gichin) (1914) "Okinawa no Bugi: Toudi

ni Tsuite Chu (The Martial Arts of Okinawa: On Toudi,

part 2)". Ryukyu Shinpo, 18 January 1914.

Shukumine S. (1964) Shin Karatedo Kyohan (New Master

Text of Karatedo). Tokyo: Nihon Bungeisha.

Tokashiki I. (1995) Okinawa Karate Hiden: Bubishi

Shinshaku (Secrets of Okinawan Karate: A New Interpretation

of the Bubishi). Naha: Gohakikai.

Tomoyori R. (1992) Karatedo no Kihon (Karatedo Basics).

Osaka: Kansai University Publishing.

Uezu A. and Jennings, J. (1982) Encyclopedia of Isshinryu

Karate, Book One.San Clement: Panther Productions.

=====================================

About

the Author - Joe

Swift is a professional translator, martial artist and

karate researcher based in Tokyo, Japan.

|

|